The Protestant Reformation Led to an Increase in Religious Art in Northern Europe

Hans Holbein the Younger's Noli me tangere a relatively rare Protestant oil painting of Christ from the Reformation catamenia. Information technology is modest, and more often than not naturalistic in style, avoiding iconic elements like the halo, which is barely discernible.

The Protestant Reformation during the 16th century in Europe about entirely rejected the existing tradition of Cosmic art, and very often destroyed as much of it as it could accomplish. A new artistic tradition developed, producing far smaller quantities of art that followed Protestant agendas and diverged drastically from the southern European tradition and the humanist art produced during the Loftier Renaissance. The Lutheran churches, as they developed, accepted a limited role for larger works of art in churches,[1] [2] and likewise encouraged prints and book illustrations. Calvinists remained steadfastly opposed to art in churches, and suspicious of pocket-sized printed images of religious subjects, though generally fully accepting secular images in their homes.

In plough, the Catholic Counter-Reformation both reacted against and responded to Protestant criticisms of art in Roman Catholicism to produce a more stringent style of Catholic art. Protestant religious fine art both embraced Protestant values and assisted in the proliferation of Protestantism, simply the amount of religious art produced in Protestant countries was hugely reduced. Artists in Protestant countries diversified into secular forms of art like history painting, landscape painting, portrait painting and still life.

Art and the Reformation [edit]

The Protestant Reformation was a religious motion that occurred in Western Europe during the 16th century that resulted in a separate in Christianity between Roman Catholics and Protestants. This movement "created a Northward-S split in Europe, where by and large Northern countries became Protestant, while Southern countries remained Catholic."[3]

The Reformation produced 2 main branches of Protestantism; i was the Evangelical Lutheran churches, which followed the teachings of Martin Luther, and the other the Reformed Churches, which followed the ideas of John Calvin and Huldrych Zwingli. Out of these branches grew three chief sects, the Lutheran tradition, as well equally the Continental Reformed and Anglican traditions, the latter two post-obit the Reformed (Calvinist) organized religion.[four] Lutherans and Reformed Christians had different views regarding religious imagery.[5] [2]

Martin Luther in Germany immune and encouraged the brandish of a restricted range of religious imagery in churches, seeing the Evangelical Lutheran Church building as a continuation of the "ancient, apostolic church".[2] The apply of images was one of the problems where Luther strongly opposed the more than radical Andreas Karlstadt. For a few years Lutheran altarpieces like the Last Supper by the younger Cranach were produced in Federal republic of germany, especially by Luther's friend Lucas Cranach, to replace Cosmic ones, frequently containing portraits of leading reformers as the apostles or other protagonists, only retaining the traditional depiction of Jesus. As such, "Lutheran worship became a circuitous ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church interior."[i] Lutherans continued the utilise of the crucifix as information technology highlighted their high view of the Theology of the Cantankerous.[two] [6] Stories grew up of "indestructible" images of Luther, that had survived fires, by divine intervention.[7] Thus, for Lutherans, "the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious image."[viii]

On the other hand, at that place was a wave of iconoclasm, or the destruction of religious imagery. This began very early in the Reformation, when students in Erfurt destroyed a wooden altar in the Franciscan friary in December 1521.[9] Later, Reformed Christianity showed consistent hostility to religious images, as idolatry, peculiarly sculpture and large paintings. Book illustrations and prints were more adequate, because they were smaller and more private. Reformed leaders, especially Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin, actively eliminated imagery from churches within the control of their followers, and regarded the great majority of religious images as idolatrous.[ten] Early on Calvinists were even suspicious of portraits of clergy; Christopher Hales (soon to exist one of the Marian exiles) tried to have portraits of vi divines sent to him from Zurich, and felt information technology necessary to explain his motives in a letter of 1550: "this is not washed ....with a view to making idols of you; they are desired for the reasons which I accept mentioned, and not for the sake of honour or veneration".[eleven]

The destruction was often extremely divisive and traumatic within communities, an unmistakable physical manifestation, frequently imposed from above, that could not be ignored. It was but for this reason that reformers favoured a single dramatic coup, and many premature acts in this line sharply increased subsequent hostility between Catholics and Calvinists in communities – for it was by and large at the level of the city, town or village that such deportment occurred, except in England and Scotland.

Merely reformers often felt impelled by strong personal convictions, every bit shown by the case of Frau Göldli, on which Zwingli was asked to advise. She was a Swiss lady who had once fabricated a hope to Saint Apollinaris that if she recovered from an illness she would donate an image of the saint to a local convent, which she did. Later she turned Protestant, and feeling she must reverse what she now saw as a wrong activity, she went to the convent church, removed the statue and burnt information technology. Prosecuted for irreverence, she paid a modest fine without complaint, just flatly refused to pay the additional sum the court ordered be paid to the convent to supersede the statue, putting her at chance of serious penalties. Zwingli's letter advised trying to pay the nuns a larger sum on status they did non replace the statue, but the eventual outcome is unknown.[12] By the end of his life, afterwards iconoclastic shows of force became a feature of the early phases of the French Wars of Religion, even Calvin became alarmed and criticised them, realizing that they had become counter-productive.[thirteen]

Daniel Hisgen's paintings are by and large cycles on the parapets of Lutheran church building galleries. Here the Cosmos (left) to the Annunciation tin be seen.

Subjects prominent in Catholic art other than Jesus and events in the Bible, such every bit Mary and saints were given much less accent or disapproved of in Protestant theology. Equally a outcome, in much of northern Europe, the Church building almost ceased to commission figurative art, placing the dictation of content entirely in the hands of the artists and lay consumers. Calvinism fifty-fifty objected to not-religious funerary fine art, such as the heraldry and effigies beloved of the Renaissance rich.[14] Where in that location was religious art, iconic images of Christ and scenes from the Passion became less frequent, as did portrayals of the saints and clergy. Narrative scenes from the Bible, especially equally book illustrations and prints, and, subsequently, moralistic depictions of modern life were preferred. Both Cranachs painted allegorical scenes setting out Lutheran doctrines, in particular a serial on Law and Gospel. Daniel Hisgen, a High german Rococo painter of the 18th century in Upper Hesse, specialized in cycles of biblical paintings decorating the front of the gallery parapet in Lutheran churches with an upper gallery, a less prominent position that satisfied Lutheran scruples. Wooden organ cases were also often painted with similar scenes to those in Cosmic churches.

Lutherans strongly defended their existing sacred fine art from a new wave of Calvinist-on-Lutheran iconoclasm in the second half of the century, equally Calvinist rulers or metropolis authorities attempted to impose their will on Lutheran populations in the "Second Reformation" of about 1560–1619.[2] [15] Against the Reformed, Lutherans exclaimed: "You black Calvinist, you give permission to blast our pictures and hack our crosses; we are going to smash you and your Calvinist priests in return".[2] The Beeldenstorm, a large and very disorderly wave of Calvinist mob destruction of Catholic images and church building fittings that spread through the Depression Countries in the summer of 1566 was the largest outbreak of this sort, with desperate political repercussions.[xvi] This campaign of Calvinist iconoclasm "provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs" in Germany and "antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox" in the Baltic region.[17] Similar patterns to the German language actions, but with the add-on of encouragement and sometimes finance from the national regime, were seen in Anglican England in the English Civil War and English Commonwealth in the side by side century, when more than damage was done to art in medieval parish churches than during the English Reformation.

A major theological difference between Protestantism and Catholicism is the question of transubstantiation, or the literal transformation of the Communion wafer and wine into the body and claret of Christ, though both Lutheran and Reformed Christians affirmed the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the former every bit a sacramental union and the latter as a pneumatic presence.[18] Protestant churches that were not participating in the iconoclasm frequently selected as altarpieces scenes depicting the Concluding Supper. This helped the worshippers to recall their theology behind the Eucharist, every bit opposed to Catholic churches, which often chose crucifixion scenes for their altarpieces to remind the worshippers that the sacrifice of Christ and the sacrifice of the Mass were 1 and the same, via the literal transformation of the Eucharist.

The Protestant Reformation likewise capitalized on the popularity of printmaking in northern Europe. Printmaking allowed images to be mass-produced and widely bachelor to the public at low cost. This allowed for the widespread availability of visually persuasive imagery. The Protestant church building was therefore able, as the Cosmic Church building had been doing since the early 15th century, to bring their theology to the people, and religious education was brought from the church into the homes of the common people, thereby forming a directly link between the worshippers and the divine.

There was also a fierce propaganda war fought partly with popular prints by both sides; these were often highly scurrilous caricatures of the other side and their doctrines. On the Protestant side, portraits of the leading reformers were popular, and their likenesses sometimes represented the Apostles and other figures in Biblical scenes such as the Concluding Supper.

Genre and landscape [edit]

After the early on years of the reformation, artists in Protestant areas painted far fewer religious subjects for public display, although there was a conscious effort to develop a Protestant iconography of Bible illustration in book illustrations and prints. In the early on Reformation artists, specially Cranach the Elderberry and Younger and Holbein, made paintings for churches showing the leaders of the reformation in ways very similar to Cosmic saints. Afterward Protestant taste turned from the display in churches of religious scenes, although some continued to exist displayed in homes. There was likewise a reaction against big images from classical mythology, the other manifestation of high style at the time. This brought about a fashion that was more direct related to accurately portraying the present times. The traditions of landscapes and genre paintings that would fully flower in the 17th century began during this period.

Peter Bruegel (1525–1569) of Flanders is the great genre painter of his fourth dimension, who worked for both Catholic and Protestant patrons. In well-nigh of his paintings, even when depicting religious scenes, most space is given to mural or peasant life in 16th century Flanders. Bruegel's Wedding Feast, portrays a Flemish-peasant wedding dinner in a barn, which makes no reference to any religious, historical or classical events, and merely gives insight into the everyday life of the Flemish peasant. Some other great painter of his age, Lucas van Leyden (1489–1533), is known mostly for his engravings, such equally The Milkmaid, which depicts peasants with milk cows. This engraving, from 1510, well before the Reformation, contains no reference to religion or classicism, although much of his other work features both.

Bruegel was also an accomplished landscape painter. Ofttimes Bruegel painted agricultural landscapes, such as Summer from his famous ready of the seasons, where he shows peasants harvesting wheat in the country, with a few workers taking a lunch break under a nearby tree. This type of landscape painting, evidently void of religious or classical connotations, gave birth to a long line of northern European landscape artists, such every bit Jacob van Ruisdael.

With the great evolution of the engraving and printmaking market in Antwerp in the 16th century, the public was provided with attainable and affordable images. Many artists provided drawings to book and print publishers, including Bruegel. In 1555 Bruegel began working for The Four Winds, a publishing firm owned by Hieronymus Cock. The Iv Winds provided the public with almost a k etchings and engravings over two decades. Between 1555 and 1563 Bruegel supplied Cock with almost forty drawings, which were engraved for the Flemish public.

The courtly style of Northern Mannerism in the 2d half of the century has been seen as partly motivated by the desire of rulers in both the Holy Roman Empire and France to discover a fashion of art that could appeal to members of the courtly elite on both sides of the religious dissever.[xix] Thus religious controversy had the rather ironic effect of encouraging classical mythology in art, since though they might disapprove, even the most stern Calvinists could not credibly merits that 16th century mythological art really represented idolatry.

Quango of Trent [edit]

During the Reformation a great departure arose between the Catholic Church and the Protestant Reformers of the north regarding the content and manner of art work. The Catholic Church viewed Protestantism and Reformed iconoclasm as a threat to the church and in response came together at the Council of Trent to constitute some of their own reforms. The church felt that much religious art in Cosmic countries (especially Italy) had lost its focus on religious subject-affair, and became too interested in cloth things and decorative qualities. The council came together periodically between 1545 and 1563. The reforms that resulted from this council are what set the ground for what is known as the Counter-Reformation.

Italian painting after the 1520s, with the notable exception of the art of Venice, developed into Mannerism, a highly sophisticated style, striving for effect, that concerned many churchman as lacking appeal for the mass of the population. Church force per unit area to restrain religious imagery affected art from the 1530s and resulted in the decrees of the concluding session of the Council of Trent in 1563 including short and rather inexplicit passages apropos religious images, which were to have nifty impact on the development of Catholic art. Previous Cosmic Church building councils had rarely felt the need to pronounce on these matters, unlike Orthodox ones which take oft ruled on specific types of images.

Statements are ofttimes made along the lines of "The decrees of the Council of Trent stipulated that art was to exist straight and compelling in its narrative presentation, that information technology was to provide an accurate presentation of the biblical narrative or saint's life, rather than adding incidental and imaginary moments, and that information technology was to encourage piety",[twenty] but in fact the actual decrees of the council were far less explicit than this, though all of these points were probably in line with their intentions. The very short passage dealing with fine art came only in the final session in 1563, equally a terminal infinitesimal and lilliputian-discussed improver, based on a French draft. The decree confirmed the traditional doctrine that images only represented the person depicted, and that veneration to them was paid to the person themself, not the image, and further instructed that:

...every superstition shall be removed ... all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust... there be nothing seen that is hell-raising, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, aught that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God. And that these things may be the more faithfully observed, the holy Synod ordains, that no one exist allowed to place, or cause to be placed, any unusual prototype, in whatever place, or church, howsoever exempted, except that epitome have been approved of by the bishop ...[21]

The number of decorative treatments of religious subjects declined sharply, as did "unbecomingly or confusedly arranged" Mannerist pieces, as a number of books, notably by the Flemish theologian Molanus, Saint Charles Borromeo and Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, and instructions by local bishops, amplified the decrees, often going into minute detail on what was acceptable. Many traditional iconographies considered without adequate scriptural foundation were in effect prohibited, as was any inclusion of classical pagan elements in religious art, and about all nudity, including that of the infant Jesus.[22] According to the great medievalist Émile Mâle, this was "the death of medieval art".[23]

Fine art and the Counter-Reformation [edit]

While Calvinists largely removed public art from religion and Reformed societies moved towards more "secular" forms of art which might be said to glorify God through the portrayal of the "natural beauty of His creation and past depicting people who were created in His epitome",[24] Counter-Reformation Catholic church continued to encourage religious fine art, but insisted it was strictly religious in content, glorifying God and Catholic traditions, including the sacraments and the saints.[25] Likewise, "Lutheran places of worship contain images and sculptures not only of Christ but also of biblical and occasionally of other saints likewise as prominent decorated pulpits due to the importance of preaching, stained glass, ornate furniture, magnificent examples of traditional and mod architecture, carved or otherwise embellished altar pieces, and liberal use of candles on the altar and elsewhere."[26] The main difference between Lutheran and Roman Cosmic places of worship was the presence of the tabernacle in the latter.[26]

Sydney Joseph Freedberg, who invented the term Counter-Maniera, cautions confronting connecting this more austere style in religious painting, which spread from Rome from nearly 1550, likewise direct with the decrees of Trent, equally it pre-dates these past several years. He describes the decrees equally "a codifying and official sanction of a temper that had come to be conspicuous in Roman civilization".[27]

Scipione Pulzone's (1550–1598) painting of the Lamentation which was commissioned for the Church of the Gesù in 1589 is a Counter-Maniera work that gives a articulate demonstration of what the holy council was striving for in the new style of religious fine art. With the focus of the painting giving direct attention to the crucifixion of Christ, it complies with the religious content of the council and shows the story of the passion while keeping Christ in the image of the platonic human.

Ten years after the Quango of Trent's decree Paolo Veronese was summoned by the Inquisition to explicate why his Concluding Supper, a huge canvas for the refectory of a monastery, contained, in the words of the Inquisition: "buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities" equally well as extravagant costumes and settings, in what is indeed a fantasy version of a Venetian patrician feast.[28] Veronese was told that he must modify his indecorous painting within a three-month menses – in fact he just changed the title to The Feast in the House of Levi, nonetheless an episode from the Gospels, simply a less doctrinally fundamental 1, and no more was said.[29] No doubtfulness any Protestant authorities would accept been every bit disapproving. The pre-existing reject in "donor portraits" (those who had paid for an altarpiece or other painting being placed within the painting) was as well accelerated; these become rare after the Council.

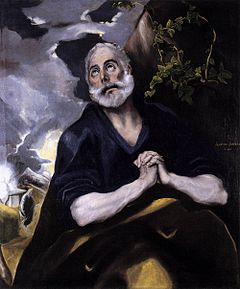

Repentance of Peter by El Greco, 1580–1586.

Further waves of "Counter-Reformation fine art" occurred when areas formerly Protestant were over again brought under Catholic rule. The churches were unremarkably empty of images, and such periods could represent a boom time for artists. The best known instance is the new Spanish Netherlands (essentially modernistic Belgium), which had been the centre of Protestantism in kingdom of the netherlands but became (initially) exclusively Catholic afterward the Spanish drove the Protestants to the north, where they established the United Provinces. Rubens was ane of a number of Flemish Bizarre painters who received many commissions, and produced several of his best known works re-filling the empty churches.[xxx] Several cities in France in the French wars of religion and in Frg, Bohemia and elsewhere in the Thirty Years War saw similar bursts of restocking.

The rather extreme pronouncement by a synod in Antwerp in 1610 that in time to come the central panels of altarpieces should only show New Attestation scenes was certainly ignored in the cases of many paintings by Rubens and other Flemish artists (and in item the Jesuits continued to commission altarpieces centred on their saints), but nonetheless New Attestation subjects probably did increase.[31] Altarpieces became larger and more easy to make out from a distance, and the large painted or gold carved wooden altarpieces that were the pride of many northern late medieval cities were often replaced with paintings.[32]

Some subjects were given increased prominence to reflect Counter-Reformation emphases. The Repentance of Peter, showing the end of the episode of the Denial of Peter, was not often seen before the Counter-Reformation, when information technology became pop as an assertion of the sacrament of Confession against Protestant attacks. This followed an influential book past the Jesuit Fundamental Robert Bellarmine (1542–1621). The image typically shows Peter in tears, as a half-length portrait with no other figures, often with easily clasped equally at right, and sometimes "the cock" in the groundwork; it was often coupled with a repentant Mary Magdalen, some other exemplar from Bellarmine's book.[33]

As the Counter-Reformation grew stronger and the Catholic Church felt less threat from the Protestant Reformation, Rome once once again began to assert its universality to other nations around the world. The religious social club of the Jesuits or the Society of Jesus, sent missionaries to the Americas, parts of Africa, India and eastern asia and used the arts as an effective means of articulating their message of the Catholic Church's dominance over the Christian faith. The Jesuits' bear on was so profound during their missions of the time that today very similar styles of art from the Counter-Reformation menses in Catholic Churches are institute all over the world.

Despite the differences in approaches to religious fine art, stylistic developments passed about as quickly beyond religious divisions as within the two "blocs". Artistically Rome remained in closer touch with the Netherlands than with Spain.

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Spicer, Andrew (5 December 2016). Lutheran Churches in Early Modernistic Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 237. ISBN9781351921169.

As it adult in north-eastern Germany, Lutheran worship became a complex ritual choreography set in a richly furnished church building interior. This much is axiomatic from the background of an epitaph painted in 1615 past Martin Schulz, destined for the Nikolaikirche in Berlin (see Figure 5.5.).

- ^ a b c d e f Lamport, Mark A. (31 August 2017). Encyclopedia of Martin Luther and the Reformation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 138. ISBN9781442271593.

Lutherans connected to worship in pre-Reformation churches, mostly with few alterations to the interior. It has even been suggested that in Germany to this 24-hour interval one finds more ancient Marian altarpieces in Lutheran than in Cosmic churches. Thus in Germany and in Scandinavia many pieces of medieval fine art and architecture survived. Joseph Leo Koerner has noted that Lutherans, seeing themselves in the tradition of the ancient, churchly church, sought to defend every bit well as reform the use of images. "An empty, white-done church proclaimed a wholly spiritualized cult, at odds with Luther's doctrine of Christ's real presence in the sacraments" (Koerner 2004, 58). In fact, in the 16th century some of the strongest opposition to destruction of images came non from Catholics simply from Lutherans against Calvinists: "Y'all black Calvinist, you lot give permission to smash our pictures and hack our crosses; we are going to smash you and your Calvinist priests in render" (Koerner 2004, 58). Works of fine art continued to be displayed in Lutheran churches, often including an imposing large crucifix in the sanctuary, a clear reference to Luther'south theologia crucis. ... In dissimilarity, Reformed (Calvinist) churches are strikingly different. Usually unadorned and somewhat defective in aesthetic entreatment, pictures, sculptures, and ornate chantry-pieces are largely absent; in that location are few or no candles; and crucifixes or crosses are besides more often than not absent.

- ^ The Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Historicist and Causes of the Reformation. New Appearance.

- ^ Picken, Stuart D.B. (sixteen December 2011). Historical Lexicon of Calvinism. Scarecrow Press. p. 1. ISBN9780810872240.

While Germany and the Scandinavian countries adopted the Lutheran model of church and state, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Hungary, what is now the Czechia, and Scotland created Reformed Churches based, in varying ways, on the model Calvin fix up in Geneva. Although England pursued the Reformation ideal in its own way, leading to the germination of the Anglican Communion, the theology of the Thirty-Ix Manufactures of the Church of England were heavily influenced by Calvinism.

- ^ Nuechterlein, Jeanne Elizabeth (2000). Holbein and the Reformation of Art. Academy of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Marquardt, Janet T.; Hashemite kingdom of jordan, Alyce A. (14 January 2009). Medieval Art and Architecture after the Eye Ages. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 71. ISBN9781443803984.

In fact, Lutherans ofttimes justified their continued use of medieval crucifixes with the same arguments employed since the Heart Ages, as is axiomatic from the instance of the chantry of the Holy Cross in the Cistercian church of Doberan.

- ^ Michalski, 89

- ^ Dixon, C. Scott (nine March 2012). Contesting the Reformation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 146. ISBN9781118272305.

Co-ordinate to Koerner, who dwells on Lutheran fine art, the Reformation renewed rather than removed the religious epitome.

- ^ Noble, nineteen, note 12

- ^ Institutes, 1:11, section 7 on crosses

- ^ Campbell, Lorne, Renaissance Portraits, European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries, p. 193, 1990, Yale, ISBN 0300046758; Hales was the brother of John Hales (died 1572)

- ^ Michalski, 87-88

- ^ Michalski, 73-74

- ^ Michalski, 72-73

- ^ Michalski, 84. Google books

- ^ Kleiner, Fred South. (i January 2010). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Concise History of Western Art. Cengage Learning. p. 254. ISBN9781424069224.

In an episode known as the Dandy Iconoclasm, bands of Calvinists visited Catholic churches in holland in 1566, shattering stained-glass windows, bang-up statues, and destroying paintings and other artworks they perceived as idolatrous.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (22 October 2009). The Reformation. Oxford Academy Press. p. 114. ISBN9780191578885.

Iconoclastic incidents during the Calvinist 'Second Reformation' in Federal republic of germany provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs, while Protestant paradigm-breaking in the Baltic region securely antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox, a group with whom reformers might have hoped to make common cause.

- ^ Mattox, Mickey Fifty.; Roeber, A. G. (27 February 2012). Changing Churches: An Orthodox, Cosmic, and Lutheran Theological Conversation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 54. ISBN9780802866943.

In this "sacramental spousal relationship," Lutherans taught, the body and blood of Christ are so truly united to the staff of life and wine of the Holy Communion that the ii may be identified. They are at the same time body and blood, staff of life and wine. This divine nutrient is given, more-over, not just for the strengthening of faith, nor just equally a sign of our unity in religion, nor merely as an assurance of the forgiveness of sin. Even more than, in this sacrament the Lutheran Christian receives the very body and blood of Christ precisely for the strengthening of the union of faith. The "existent presence" of Christ in the Holy Sacrament is the means by which the wedlock of faith, effected by God's Word and the sacrament of baptism, is strengthened and maintained. Intimate union with Christ, in other words, leads directly to the near intimate communion in his holy torso and claret.

- ^ Trevor-Roper, 98-101 on Rudolf, and Strong, Pt. 2, Chapter 3 on French republic, especially pp. 98-101, 112-113.

- ^ Art in Renaissance Italian republic. Paoletti, John T., and Gary M. Radke. Pg. 514.

- ^ Text of the 25th decree of the Council of Trent

- ^ Edgeless Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1660, chapter VIII, especially pp. 107-128, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-nineteen-881050-4

- ^ The decease of Medieval Art Extract from book by Émile Mâle

- ^ Art of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Nosotro, Rit.

- ^ The Fine art of the Counter Reformation. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ a b Lamport, Mark A. (31 August 2017). Encyclopedia of Martin Luther and the Reformation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 138. ISBN9781442271593.

- ^ (Sidney) Freedberg, 427–428, 427 quoted

- ^ "Transcript of Veronese's testimony". Archived from the original on 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2007-03-26 .

- ^ David Rostand, Painting in Sixteenth-Century Venice: Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, second ed 1997, Cambridge Upwards ISBN 0-521-56568-5

- ^ (David) Freedberg, throughout

- ^ (David) Freedberg, 139-140

- ^ (David) Freedberg, 141

- ^ Hall, pp. 10 and 315

References [edit]

- David Freedberg, "Painting and the Counter-Reformation", from the catalogue to The Age of Rubens, 1993, Boston/Toledo, Ohio, online PDF

- Freedburg, Sidney J. Painting in Italian republic, 1500–1600, 3rd edn. 1993, Yale, ISBN 0300055870

- James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Fine art, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- Michalski, Sergiusz. Reformation and the Visual Arts: The Protestant Image Question in Western and Eastern Europe, Routledge, 1993, ISBN 0-203-41425-X, 9780203414255 Google Books

- Noble, Bonnie (2009). Lucas Cranach the Elderberry: Art and Devotion of the German Reformation. University Press of America. ISBN978-0-7618-4337-v.

- Roy Stiff; Fine art and Power; Renaissance Festivals 1450-1650, 1984, The Boydell Press;ISBN 0-85115-200-vii

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh; Princes and Artists, Patronage and Credo at Four Habsburg Courts 1517-1633, Thames & Hudson, London, 1976, ISBN 0-500-23232-6

Further reading [edit]

- Avalli-Bjorkman, Gorel. "A Bolognese Portrait of a Butcher." The Burlington Magazine 141 (1999).

- Caldwell, Dorigen. "Reviewing Counter-Reformation Art." 5 Feb. 2007 [1].

- Christensen, Carl C. "Art and the Reformation in Frg." The Sixteenth Century Journal Athens: Ohio Upwardly, 12 (1979): 100.

- Coulton, G G. "Art and the Reformation Reviews." Art Message xi (1928).

- Honig, Elizabeth. Painting and the Market in Early on Modern Antwerp. New Oasis: Yale UP, 1998.

- Koerner, Joseph L. The Reformation of the Image. London: The Academy of Chicago P, 2004.

- Knipping, John Baptist, Iconography of the Counter Reformation in the Netherlands: Heaven on Earth 2 vols, 1974

- Mayor, A. Hyatt, "The Art of the Counter Reformation." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Message 4 (1945).

- Silver, Larry. Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: the Ascent of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market. Philadelphia: Academy Pennsylvania P, 2006.

- Wisse, Jacob. "The Reformation." In Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000- [2] (October 2002).

External links [edit]

- Review of The Reformation of the Prototype by Joseph Leo Koerner, by Eamon Duffy, London Review of Books

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_in_the_Protestant_Reformation_and_Counter-Reformation

0 Response to "The Protestant Reformation Led to an Increase in Religious Art in Northern Europe"

Post a Comment